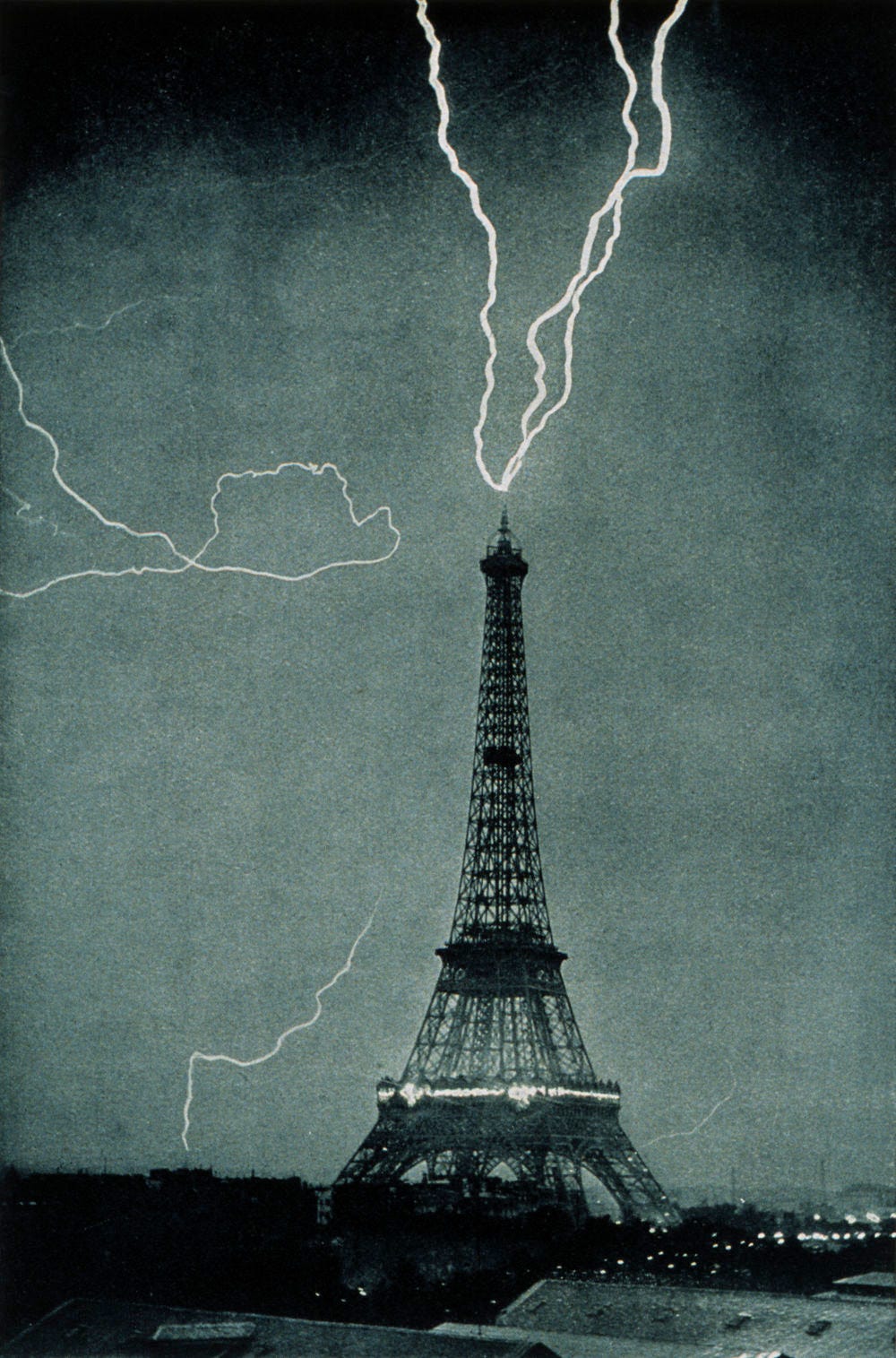

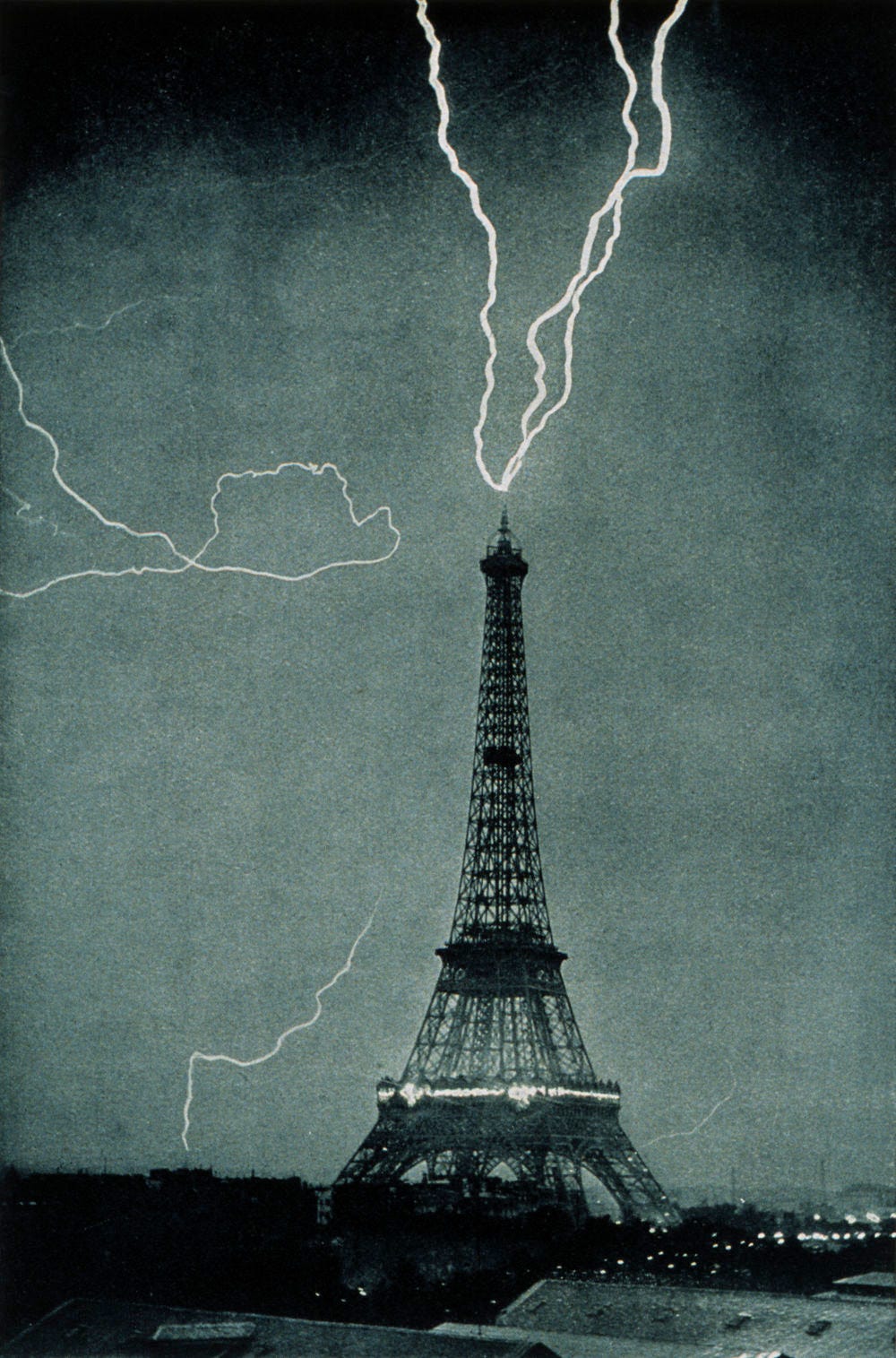

This is a follow on piece from Lucy Letby: waiver of privilege? It is mainly about waiver in a criminal context. The rules around waiver are more developed in the civil cases, since waiving privilege there is not quite as catastrophic to life, liberty and freedom, so it does happen.A document or communication is “once privileged, always privileged”. The principle that a client should be free to consult his legal advisers without fear of his communications being revealed is a fundamental condition on which the administration of justice as a whole rests. Legal professional privilege is the predominant public interest to be upheld, even where the client no longer has any recognisable interest in preserving the confidentiality or has died, or, in the case of a company, been dissolved.— Archbold on Evidence, 12-14You come at the king, you best not miss.— Omar Little, The WireUnusually, the JC made a bit of a splash when a recent piece on waiver of privilege in the Lucy Letby case caught the attention of the Double Jeopardy: Law and Policy podcast.After the usual introductory blancmange, the article settles down and looks at the case of R v Singh which seems to reverse the sacred principle that no judicial officer can come between a client and her lawyer: that all their words, notes, letters, suggestions, gestures, innuendoes and privately-communicated semaphores may forever, and for all purposes, stay private, except where the very contents of a privileged communication themselves are the issue before the court — if, for example, a defendant appeals on the grounds that she was given negligent advice.Until 2017, there were discrete and unobjectionable rules dealing with two commonly “time wastey” scenarios: firstly, were a defendant has parted ways with trial counsel and appointed new representatives for an appeal; secondly, where the defendant wishes to blame her conviction on her trial representatives doing a bad job.This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.While they are often related, these scenarios are nonetheless conceptually distinct.The rules, in essence, are firstly, that new counsel must confirm to the court they have spoken thoroughly with outgoing counsel and fully understand the background and their strategy at the original trial — this is the rule in R v McCook — and secondly, if the defendant wishes to blame her conviction on her trial representatives’ “inadequate representation”, then she must waive legal privilege in her discussions with the trial representatives to the extent needed for the Court to determine whether the trial representatives were to blame or not. This principle comes from a case called R v Frost-Helmsing.But in 2017, those sensible rules got tangled up with the Court of Appeal’s notorious aversion to hearing fresh evidence in the case of R v Singh. There ought to be a clap of thunder, a lightning bolt and a blood-curdling scream, by the way, whenever anyone says “fresh evidence”, such is the Court’s aversion to it.Now, when

Episode Details

About This Episode

This is a follow on piece from Lucy Letby: waiver of privilege? It is mainly about waiver in a criminal context. The rules around waiver are more developed in the civil cases, since waiving privilege there is not quite as catastrophic to life, liberty and freedom, so it does happen.A document or communication is “once privileged, always privileged”. The principle that a client should be free to consult his legal advisers without fear of his communications being revealed is a fundamental conditio...